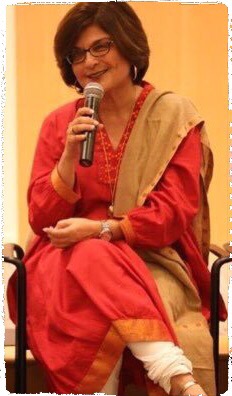

‘The Pakistani State Should Not Define People’s Religion for Them’ Farahnaz Ispahani

Raza Rumi: Your book shows how the total size of Pakistan’s minorities declined from 1947 to the present levels of 3.4%. Was it a deliberate cleansing or an out-migration?

Farahnaz Ispahani: The Pakistani state has failed to protect religious minorities from its earliest days. The violence that attended partition resulted in a massive movement of population and virtual ethnic cleansing, especially in Punjab. East Punjab had very few Muslims left and Hindus and Sikhs were forced out of western Punjab.

It was a combination of frenzy generated by politics of communal hatred and other factors, including the desire of some to create a Pakistan very different from what Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah envisaged.

My book traces the history of Pakistan’s religious minorities. The first stage in the history reflected forced changes in demographics that significantly diminished the proportion of minorities in the population – what I call ‘Muslimisation.’

The last census before Pakistan’s independence, in 1941, counted a healthy 20.5% of non-Muslims – Christians, Sikhs, Parsis and Hindus – in what was then West Pakistan, the present territory of Pakistan. By the time of the census in 1951, four years after partition, this number drastically reduced to a mere 1.7% Hindus, 1.4% Christians and a negligible figure relating to the Sikhs.

The process of ‘purifying’ the population did not end there. Pakistan’s Christians and Parsis have gradually emigrated from the country and the exodus continues to this day.

Ahmadis were deemed Muslim by the state until 1974 when they were declared non-Muslims for legal purposes through a constitutional amendment. Since then, they have been among the groups leaving the country to seek refugee status in other countries.

Violence against Shias since the 1990s has also forced them into the list of groups that are part of the exodus. The United Nation’s refugee agency UNHCR reports an increase in asylum seekers arriving from Pakistan to 1,489 in 2013, up from just 102 in 2012. Most are Christians or members of the Ahmadiyya sect. Shias are increasingly growing in this number now. Hazara Shias from Balochistan are risking life and limb on risky routes on boats from Indonesia to Australia. Other Shias are applying for asylum in the West as well.

During Zia-ul-Haq’s Islamisation drive, he used laws, social norms and fear to create the most inhospitable conditions for non-Sunni Muslim Pakistanis. He accelerated the anti-Ahmadi persecution and began the anti-Shia drive.

Raza Rumi: Could the creation of Bangladesh may also have played a part here? Should we not factor that in while interpreting the data?

Farahnaz Ispahani: East Pakistan had a healthy percentage of Hindus even after the partition. They were a vibrant and active political minority. For many years after independence, the Hindus of East Pakistan had a strong voice in keeping the culture of politics secular to avoid what was happening in the western wing of the country.

The fear, suspicion and almost visceral hatred of Indians and Hindus, of dictators like Ayub, set the tone against the Bengalis and led to the separation of East and West Pakistan.

Several massacres of Hindus in East Pakistan were reported, especially immediately after the Hazratbal incident in 1965, culminating in the tragic events of 1971. The loss of East Pakistan and the independence of Bangladesh resulted in the loss of a sizeable chunk of our minority population.

Raza Rumi: Your book also asserts that Jinnah wanted a modern and tolerant Pakistan. It is important to remind Pakistanis about the original vision. Do you agree?

Farahnaz Ispahani: Absolutely. Jinnah’s speeches and comments showed his absolute belief in the necessity of a secular government. His August 11, 1947 (speech) was a clear statement of the principles of the new state and he declared that religion should have nothing to do with the business of state. But my research and analysis bears out that the rot set in very early and an effort was launched to roll back Jinnah’s vision.

Dissemination of Jinnah’s August 11, 1947 (speech) was limited by the government he headed as governor-general. The Objectives Resolution (which is part of the current constitution of Pakistan), moved by Pakistan’s first prime minister Liaquat Ali Khan on March 7, 1949, and passed by the Constituent Assembly on March 12, 1949, declared Pakistan’s objective to be the creation of an Islamic state.

The exclusivist religious tendencies identified under Pakistan’s first prime minister were drastically different from the principles of religious inclusion enunciated by Pakistan’s founder Jinnah. The Objectives Resolution defined Pakistan’s national objective to be a state governed “in accordance with the teachings and requirements of Islam as set out in the holy Quran and Sunnah.”

There was a promise to the minorities too that “adequate provision shall be made for the minorities to freely profess and practice their religions and develop their cultures.” But the door had opened for theologians to argue that even this could only be done within the confines of established religious practice from earlier times.

Secular leaders such as Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy made prophetic warnings about the country having embarked on a self-destructive course.

Suhrawardy said at the time of the debate over the Objectives Resolution, “A time will come when this state will destroy itself… If Pakistan eliminates non-Muslims from its folds and forms a Muslim state, Islam will be destroyed in Pakistan.” He obviously meant the tolerant and live-and-let-live version of Islam.

The then leader of the opposition, Sris Chandra Chattopadhyaya, a Hindu, said: “The state must respect all religions: no smiling face for one and askance look to the other. The state religion is a dangerous principle. Previous instances are sufficient to warn us not to repeat the blunder. We know people were burnt alive in the name of religion.”

Raza Rumi: What would be the key legislative changes required to improve the status of minorities?

Farahnaz Ispahani: As originally conceived, Pakistan was, at the very least, not intended to discriminate among various Muslim denominations, and non-Muslim minorities too were assured of equal rights as citizens. However, things have changed over the last several decades.

The use of Islamic slogans and cries of “Islam in danger” during the 1946 elections preceding independence, and in defining Pakistani nationhood immediately after independence, resulted in a situation where liberal leaders slowly conceded space to the Islamists, most of whom had no role in the struggle for Pakistan.

Therefore, what came after was not surprising as I show in my book.

The Pakistani state must start legislating repeal of religion-based laws that are difficult to implement any way and are used by extremist vigilantes to legitimise their pogroms. There must be revision of the blasphemy laws and a concerted campaign to punish those who take the laws into their own hands and attack others on grounds of religion.

The repeal of the anti-Ahmadi legislation, which prescribes punishments for Ahmadis engaging in any act that might make them appear as Muslims, is another necessary step. Anyone who considers himself of a certain faith should be able to live openly and, without fear, practice that faith. People have the right to think that someone else’s faith is not compatible with their faith, but it is not the state’s business to define people’s religion for them.

Removing constitutional provisions that state that only a Muslim can be president of Pakistan and the clause more recently inserted in the 18th amendment to the constitution, which asserts that only a Muslim can be the prime minister of Pakistan, would be other necessary legal changes for Pakistan to conform to its obligations under the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

I know it is a difficult list to implement, but we have to start talking about these changes today to be able to accomplish them at some point in the future.

Raza Rumi: How can the abuse of blasphemy law be averted?

Farahnaz Ispahani: Minorities are falsely charged or victimised under blasphemy laws routinely. Sometimes people settle personal scores through false blasphemy accusations.

The blasphemy law is a man-made law but its supporters describe it as a divine law, which makes any discussion about it impossible. Like other man-made laws, this law should be subject to debate and reconsideration. Until the complete overhaul – or revision or repeal – of the law is possible, there should be very strict penalties for the abuse of any citizen in the name of blasphemy.

Raza Rumi: Your party was in power for five years, why could it not make changes to the constitution and laws?

Farahnaz Ispahani: I wrote this book as a researcher, not as spokesperson for a political party. If you are referring to the Pakistan Peoples Party, it is important to remember that its last term in office comprised a coalition government. Partnering with other parties, including religious party like Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, made major reform difficult.

We did pass the 18th amendment to the constitution with consensus, which gave the provinces autonomy and access to their own resources and monies and much more, but we could not change any laws without the consensus of our coalition partners.

Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto recognised the need for changing some of these laws and Bilawal Bhutto Zardari continues to periodically emphasise the need for change. But I admit that we are nowhere near rolling back curtailment of minorities’ rights under the banner of Islamisation at this stage.

Raza Rumi: Do you see common themes with respect to treatment of minorities in Pakistan, India and Bangladesh?

Farahnaz Ispahani: The persecution of religious minorities has become a global issue today. The issue of religious freedom around the world deserves urgent attention, which it has not been given in the past several decades. All over the world, religious minorities are being threatened by communal majoritarianism – the majority denying minorities the right to practice their religion in absolute freedom.

In our region, we see organised and small, but virulent members and groups of India’s Hindu majority, target the Muslim and Christian minorities in particular. In Myanmar and Sri Lanka, you see the majority Buddhists treat the Muslim minority, especially the Rohingya, and also the Christian Sri Lankans, with violence. In Bangladesh, the Hindu community is under attack from extremist Muslims as are secular bloggers and liberal journalists. Christians are also under pressure.

However, no other country in our region has the inbuilt constitutional bars on non-Muslim and minority Muslim citizens on the scale that Pakistan has. It is a time of great unease throughout South Asia.

Raza Rumi: If you were back in power as a minister, what would you do to curb extremism in Pakistan?

Farahnaz Ispahani: A mere minister could do very little at this juncture. It would take a civilian leader of strength, courage and vision, who also has the backing of our armed forces, to slowly change the laws and the narratives in the society.

Even if we began today, I fear it would take decades. But the longer we wait, the more fraught with danger the situation becomes, not only for Pakistan’s religious minorities – including Muslim minorities – but for the viability of the state as a whole.

The Interview is originally published by The Wire. The link to interview is Farahnaz Ispahani interview with Raza Rumi

Raza Rumi is consulting editor at The Friday Times in Pakistan. He teaches at Ithaca College and Cornell Institute of Public Affairs.

Comments 1

Absolutely I agree with author, I think this is irony that minorities are living in a worst conditions in Pakistan and this is a huge shame for the country which claims as Islamic State. state must be neutral in its political affairs its Constitution its other laws and institutions must be neutral there must not be any kind of religious influence in state affairs. its best for Pakistan to provide all basic human rights to its Nation without any racial, religious or any other discrimination. well initiative intellectual society of Pakistan must come forward and advocate this Idea. appreciable…